Trinity College Dublin Public Humanities Workshop – May 2017

Over the past two days (May 23-24, 2017) I attended the Public Humanities Workshop at the Long Room Hub in Trinity College Dublin (TCD), Ireland, funded by the DARIAH-EU project and the ADAPT Centre. It brought together academics, librarians, cultural heritage specialists, industry professionals and public administrators from Ireland, Belgium and Poland to discuss many themes in the area of public history and digital humanities.

The sessions involved a balance on topics of academic insights, project case studies, and best practices. I will summarise what I took away from the Workshop for my own personal development, but also as an attempt to share some of themes and ideas that arose from this international and interdisciplinary gathering.

What is Public history?

The first main topic of discussion was differentiating between “shared authority” and “a shared authority” in regards to public history. What I learned from Drs. Georgina Laragy and Claran O’Neill from the School of Histories and Humanities at TCD, was essentially:

- Public history is history outside of academia. They talked about how public history centres on how in the present day we can “use” the past. It is a collaborative effort to discover, explore, contextualise, and learn about history.

- Sharing authority is about collaboration, it is about equal partnership between parties such as two historians.

- A shared authority refers to the historian and public working together to interpret and create meaning.

Case study: Open Monuments Project (Poland)

Klaudia Garbowska from Creative Commons Poland discussed the Open Monuments project, which involved crowdsourced contributions to a database of information about Polish monuments. The project involved garnering public participation from an “Open Data Day” event, with 5,000 people from which they were able to gain 400 registered users for their monuments database.

She noted that some of the key factors leading to the success of the project were:

- They were audience focused. They conducted a survey to find out who their database users were (e.g., tourists, academics, teachers, activists, NGOs, and cultural institutions).

- They worked with cultural institutions who were open and happily engaged in a shared authority of public history collaboration.

- They looked at what people wanted rather than what they assumed they wanted. In other words, they had a bottom-up rather than top-down view of public history creation.

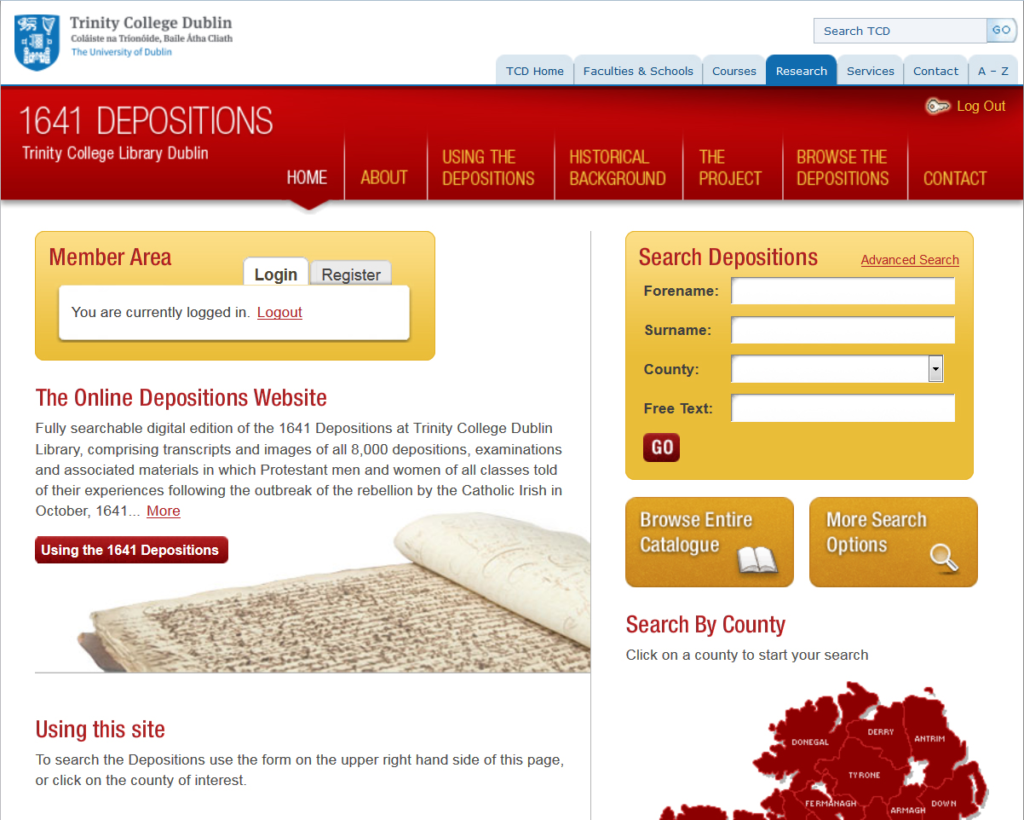

Case study: 1641 Depositions Project (Ireland)

Dr. Jane Ohlmeyer, Director of the Trinity Long Room Hub and project lead of the 1641 Depositions, discussed the crowdsourced digitization of approximately 8,000 witness testimonies of experiences from the 1641 Irish rebellion. She highlighted how this project was interdisciplinary in that it involved collaboration among historians and computing scientists (aka digital humanities).

Dr. Ohlmeyer mentioned that some of the challenges including:

- scholars from both disciplines had different vocabularies, which caused difficulties in understanding one another,

- there were some missed opportunities resulted from not engaging with the computing scientists earlier, before some key decisions were made, and

- “technology cannot solve everything, because it’s a machine.” In other words, the system is only as smart as the program and it cannot (in the current state of the art) be used to replace human semantic reasoning that historians bring to the table.

Some of the benefits technology brought to the 1641 Depositions included:

- Increased public access, which was approximately 20 people viewing the documents per year to 23,000+ registered users

- The algorithms uncovered patterns that historians may not have seen and could lead to new investigations (e.g., the number of widows)

Practical Considerations for Public History Projects

Using standardised metadata in digital library catalogues

Tim Keefe, Head of Digital Resources and Imaging Services at TCD, talked about the importance of metadata in library cataloguing. He explained many students and librarians are wary of metadata and what it means, but he showed how powerful metadata is because it can lead to linked data (resources) and substantially help people find what they’re looking for. Digitising content is almost useless if it cannot be found through metadata. Keefe also pointed out that it’s not only about using metadata, but correctly using standardised metadata for consistency and facilitating future access.

Project management of funded digital humanities project

Gemma Reid, Quarto Collective, outline the common process and project management considerations for digital humanities projects.

The common pattern of steps in funded projects are:

- Secure funding for a project

- Digitising historical material/artefacts

- Creating a website to showcase the digitised material

- Project completion

Her advice for successful sharing authority on projects involves:

- Establishing trust between participating parties

- Outlining clear roles and responsibilities

- Determining relevant outcomes

- Being flexible

- Evaluating the project

- Finding the right source of funding

She, along with other speakers, that funded DH projects are often very impactful for a short period of time, but there is a challenge with sustainability (funding) and ongoing maintenance and participation. As Klaudia Grabowska said, many DH projects often become “ghost websites”. They websites exist, but quickly become stale and forgotten about.

Public History Projects Presented

- New Panorama of Polish Literature, Bartłomiej Szleszynski, the Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences

- A Digital Repository for Dublin City Libraries and Archives, Ellen Murphy, Dublin City Library and Archives, Ireland

- St. Andrews Records Project, Corin Deinhart and Tim Murtagh, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland,

- Belgian Refugees 14-18, Martine Vermandere, Amsab-Institute of Social History, Belgium

- Derry City Walls Project, Mark Lusby, Coordinator, Friends of the Derry Walls, Northern Ireland

Key learnings

The presentations and break out discussions resulted in a handful of recurring themes/thoughts:

- The importance of creating trust between the general public and institutions

- Ensuring clear, professional (documented) communication among project partners

- Building and sustaining relationships between the disciplines (e.g. history, humanities, computing science)

- Finding ways that momentum and funding in public history projects can be sustained

- The importance of considering the audience or “end user” of the public history works early on in the project

- Building a community of interested people in a public history project from the beginning instead of finding potentially interested people at the end

- Considering who are you crowdsourcing for and why are you crowdsourcing information

What are your thoughts on public history projects? Do you know of any good examples of successful projects from around the world? Please share in the comments section below!